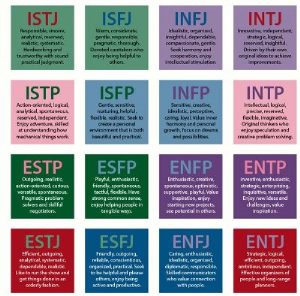

In a professional environment or out of personal curiosity, we’ve all taken personality tests that indicate our strengths and weaknesses. Why are those reductive tests so popular and in use? In David Epstein book ‘Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World‘, the author takes the position that it respond to our and organisation needs to classify us and pigeonhole us.

“A lucrative career and personality quiz and counseling industry survives on that notion. “All of the strengths-finder stuff, it gives people license to pigeonhole themselves or others in ways that just don’t take into account how much we grow and evolve and blossom and discover new things,” . “But people want answers, so these frameworks sell. It’s a lot harder to say, ‘Well, come up with some experiments and see what happens.’”

On one hand I find those tests quite insightful and they generate useful thinking about oneself and what we should reinforce or change; on the other hand it is true that they tend to classify us. By the way, the best advice is certainly not to try to improve weaknesses but rather to further enhance those strengths that make us so specific.

Organisations are then advised to seek diversity (i.e. a set of people which results to the test spread nicely across categories), and may outright reject applications on the basis of test results.

Those tests are an extremely reductionist approach to our personality and they also don’t account at all on the fact that we may evolve. Taking important decisions on their basis and letting them classify ourselves in categories is certainly excessive. They should remain as an interesting insight in our personality, but should not be used beyond a certain limit.