I recommend highly the book ‘Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World‘ by David Epstein. It has provided quite a few interesting insights for me, which will be the subject of a few following posts.

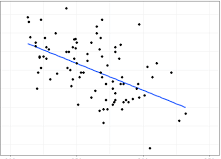

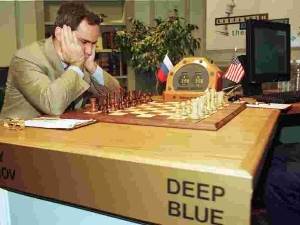

For those that have been following this blog, I have expressed many times that the Collaborative Age calls for generalists, contrary to the specialists fostered by the Industrial Age (for example here and here). This book confirms this hint in a very convincing way and goes beyond to show that complex systems can only be dealt with by generalists. And that being a specialist can be quite dangerous in terms of decision-making beyond the bounds of specialization validity.

“Highly credentialed experts can become so narrow-minded that they actually get worse with experience, even while becoming more confident— a dangerous combination.”

And specialization can indeed lead to poor real-life outcomes. For example, “One revelation in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis was the degree of segregation within big banks. Legions of specialized groups optimizing risk for their own tiny pieces of the big picture created a catastrophic whole. To make matters worse, responses to the crisis betrayed a dizzying degree of specialization-induced perversity.”

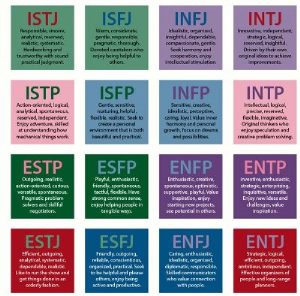

This realization is pervading more and more organisations and society when it comes to choosing someone to lead a complex endeavor. The best candidates are generalists, or at least people who have been exposed to many things beyond their main area of interest. “the most common [path to excellence] was a sampling period, often lightly structured with some lessons and a breadth of instruments and activities, followed only later by a narrowing of focus, increased structure, and an explosion of practice volume.”

I have always been convinced, and I am more and more convinced, that the rounded individual exposed to largely varied experiences and fields of knowledge is the new type of leader we will be looking for in an increasingly complex Collective Age. And this is probably the biggest challenge of our learning and academic institutions today.